The opportunity for teachers to ply their trade in the international school setting offers many unique experiences, both professional and personal. From the professional perspective, none is more rewarding than engaging culturally diverse groups of students in their learning on a day-to-day basis. Every student in the class brings their own unique language experiences, beliefs and values, along with their travel and unique third-culture experiences. In these settings, the opportunity exists for teachers to extend their repertoire of teaching practice, to ensure all students are engaged in the learning journey in their classes.

As a teacher, one quickly learns to see students in the class for what they can do, and what they bring to the table in terms of classroom discussions, group work and dynamics. Additionally, each student has a unique view of classroom behavioural ‘norms’ through their own cultural lens. Some cultures have very few teacher-student interactions in the classroom, whilst in others, this is a constant. The latter can be quite a shock for students from particular cultures, and take some time to adjust, extending the well-known ‘silent period’. Often these students become the most outspoken in the class!

Viewing curriculum outcomes through various cultural lenses represented in the class is key to a teacher effectively engaging the students in their international school classes. Valuing each and every student’s views or experiences, and positively acknowledging the political and economic systems from which they come is paramount to a positive and engaging classroom culture, based upon the saying “just because it is different, does not make it wrong”.

The practicalities in terms of ‘scaffolding up’ for students whose first language is not the language of instruction at the school is a vital aspect of teaching in the international school sector. As teachers know, schools have various approaches to catering to students whose first language is not the language of instruction, from fully-sheltered language schools, to partially sheltered programs, and most recently the much-espoused collaborative teaching (co-teaching) domain. Having been fortunate enough to experience all three of these approaches, a well-organised and data-driven co-teaching program is the most effective for these students, both in terms of the all-important student well-being, along with academic performance. In short, in an effective co-teaching program, students feel connected to their school as they are not being sheltered away from the mainstream cohort for language lessons. In turn, students whose first language is the language of instruction are always in awe of what their peers achieve on a daily and hourly basis, this in turn makes the students in question extremely proud of their achievements, and this pride is clearly validated as they are seeing the academic bar which is set in their mainstream classrooms each and every lesson. Students rarely linguistically fossilise in effective co-teaching programs.

An effective co-teaching program in this context requires staff who are truly willing to share, collaborate and build professional relationships, through co-planning, co-teaching, co-assessing and co-reflecting through regular meetings (See Cycle of Collaboration graphic below). Having co-taught in this context across Year 6-8 Science and Humanities classes for six years, rest assured that co-teaching is the best professional development a teacher will ever have, and it is daily! Subject teachers become excellent academic language teachers, and language co-teachers become quite confident subject teachers. Effective co-teaching programs are first and foremost relationship-based, and without positive and collaborative staff relationships much effectiveness for effective student learning is sadly lost.

A Cycle of Collaboration

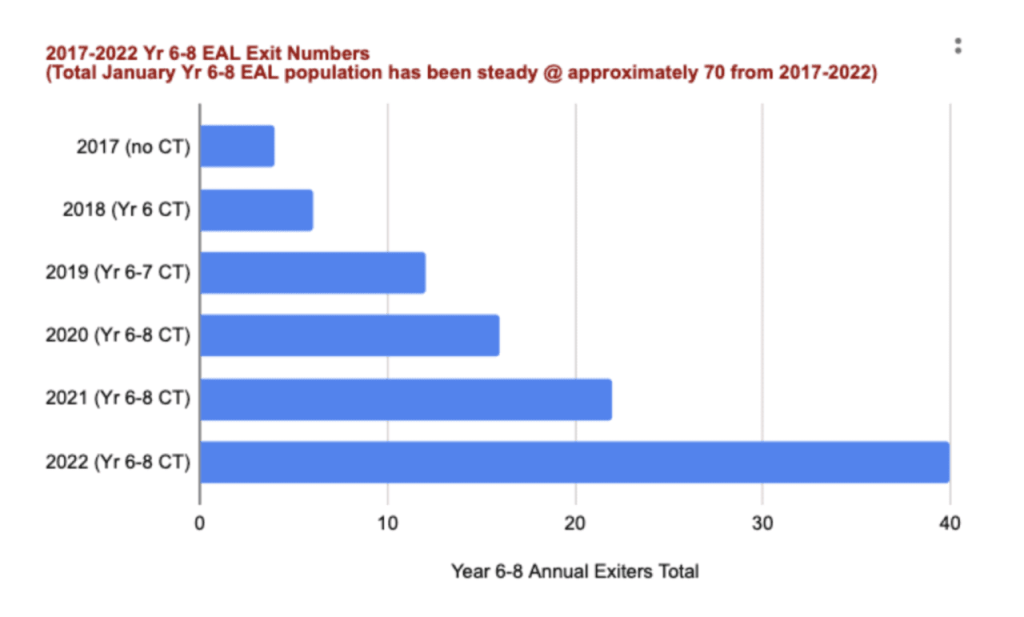

Students’ academic language proficiency progression is accelerated exponentially in effective co-teaching programs in upper primary and middle school year levels (see data provided below – school name withheld), however, the catch is students who are in the beginning phase of their academic language acquisition journey can for various reasons become lost in the shuffle and may require sheltered instruction to accompany their mainstream class experiences. Experience and data demonstrate that intermediate and advanced academic language level students thrive in true co-teaching environments. This linguistic progression is doubled down in terms of acceleration through an effective mother tongue program at the school, ensuring additive bilingualism is occurring.

The role of the co-teacher is to flesh out the academic language embedded in each unit of work and explain to students the regular independent study habits required to learn the required tier two and tier three academic language needed for each unit of work, prior to and during the teaching of the unit in question. Furthermore, effective co-teachers provide resources such as comprehension, pre-reading/viewing activities and provide notetaking scaffolds, along with support resources for production tasks such as structural scaffolds (relevant to text type), sentence frames and writing samples as required. There is much more to co-teaching than this brief overview, however these are very sound pillars upon which to build, along with knowing each student’s current year-level appropriate academic language proficiency in the reading, writing, speaking and listening domains. The wonderful by-product is that all students benefit from these ‘scaffold up’ resources, not only the students whose first language is not the school’s language of instruction.

Next time you apply for an international school role, ask if the school has a co-teaching program, because it is one of the most satisfying teaching experiences a teacher can enjoy, and proudly watch your students fly.

This article was submitted by Tim Hudson, an academic language acquisition expert with 34 years of experience in teaching and leading EAL and other subject department teams at the secondary level in international school settings, including Shanghai American School and more recently the Australian International School in Singapore. Tim was also instrumental in building the very successful international student program at Fraser Coast Anglican College in Queensland, Australia.

He is currently on sabbatical, offering tutoring services for EAL learners and consultancy services for schools in the EAL domain.

His skills include curriculum design, assisting schools new to this domain in developing context-appropriate EAL programs, and enhancing existing EAL programs in schools. He has extensive experience providing professional development to subject-teaching teams across the curriculum in the realm of academic language acquisition and has a passion for EAL co-teaching. You can reach him at aclangedge@gmail.com